BISAC NAT010000 Ecology

BISAC NAT045050 Ecosystems & Habitats / Coastal Regions & Shorelines

BISAC NAT025000 Ecosystems & Habitats / Oceans & Seas

BISAC NAT045030 Ecosystems & Habitats / Polar Regions

BISAC SCI081000 Earth Sciences / Hydrology

BISAC SCI092000 Global Warming & Climate Change

BISAC SCI020000 Life Sciences / Ecology

BISAC SCI039000 Life Sciences / Marine Biology

BISAC SOC053000 Regional Studies

BISAC TEC060000 Marine & Naval

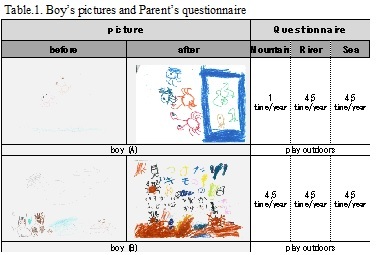

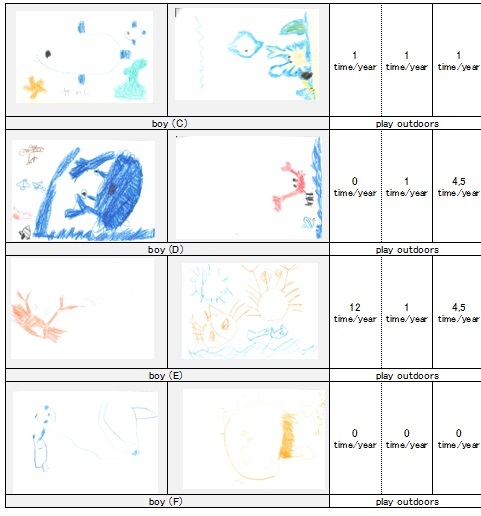

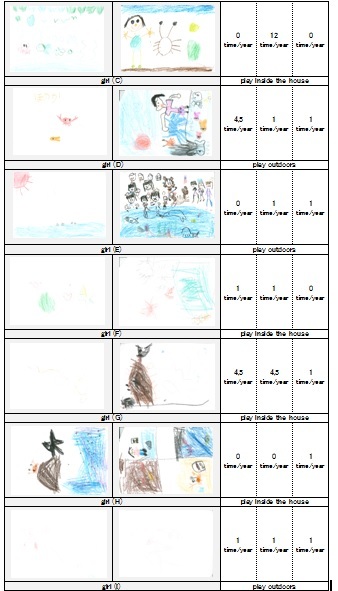

In this study, an environmental education program for preschool children was conducted at the seaside, and its effects were evaluated by examining pictures of marine environments drawn by the children before and after the program. The purpose of the education program was to heighten children’s levels of interest in the sea, encourage them to perceive the seaside as a space for play, and increase their familiarity with it. When the children’s pictures drawn before and after the program are compared, the most striking difference is whether or not people are included in the picture. Of the 16 kids who drew both pictures, only one put a person in the picture before the program, but this increased to six afterward, and five of these depicted “sea animals and me” together. There was also one who drew “sea animals, my friends, and me,” and another who drew a four-panel comic strip telling a story. In addition, eight of the 16 children drew living things small and weakly beforehand, but more powerfully and dynamically afterward. As we have seen, the hands-on seaside experience during this education program acted on five senses and caused a change in their internal mental models. It also enabled them to perceive a connection between the sea and themselves, and in some cases to understand and express the relationship between human beings and the sea and between other children and themselves. In future studies, we intend to increase the number of case studies of this type of program.

environmental education, preschool children, drawings

I. Introduction

Japan is a maritime nation with the world’s sixth largest sea area (in terms of exclusive economic zone) [1][2]. Japan promulgated the Basic Act of Ocean Policy on 20 July, 2007. According to the Act, Japan’s citizen are required an effort to proceed environmental education in coastal zone as follows: ”The State shall take necessary measures, in order that citizens shall have a better understanding of and deeper interests in the oceans, to promote school education and social education with regard to the oceans, propagation and enlightenment of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and other international agreements as well as international efforts to realize the sustainable development and use of the oceans, and popularization of ocean recreation.”[3]. We have been counteracting this by conducting environmental education programs (including hands-on nature experience activities) at the seaside for many years, and have been promoting children’s familiarity with sea creatures and other aspects of the seashore environment [4]. In an endeavor such as this one, education for young children is thought to be particularly important in providing experiences that shape later emotional development and character formation [5]. Therefore, we expect that fostering familiarity with the marine environment in young children will lead them to remain engaged with it for many years thereafter. On the other hand, there are challenges in that verbal communication with young children is difficult, as is objective evaluation of the effects of what they learned and experienced. To address this, in this study we focused on drawing as a means of learning about children’s perceptions, and developed a method of evaluating the educational programs’ effects. Specifically, before and after carrying out an environmental education program, we asked children to draw pictures on the theme of the sea, gauged children’s internal psychological changes from differences in the content of the pictures, and assessed the effects of the learning sessions.

II. Education program approach

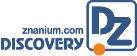

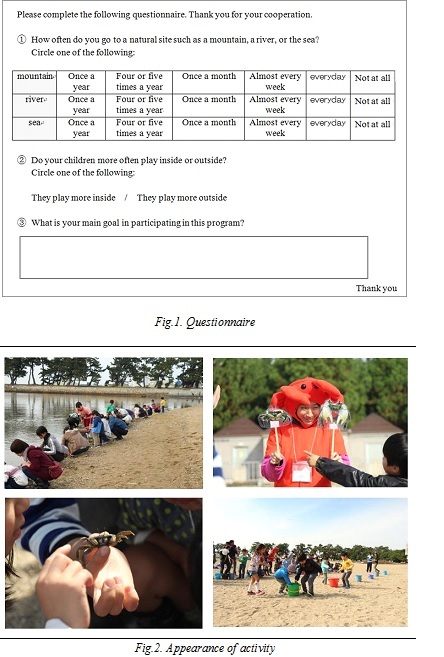

Local preschool children (aged three to five) participated in a 1.5-hour education program at Takasago Seaside Park in Takasago, Hyogo Prefecture. Before and after the program, the children were given approximately 10 minutes to draw a picture on the theme of “the sea.” Separately, parents and guardians were asked questions on topics such as frequency of engagement with the nature, their reasons for participating in this program, and their impressions of the program (fig.1). Two measures were taken to make the program interesting. One was to introduce elements of the fantasy world, in light of the idea that early childhood education should involve all five senses, and drawing inspiration from the “Skogsmulle” [6] experiential nature-learning program developed in Sweden. In this program a Crab Fairy in a crab costume appeared, and sought to boost children’s interest in and familiarity with the marine environment. The second measure was to divide the 1.5-hour learning session into four activities so that children would not grow bored. These were (fig.2): (1) An icebreaker that got kids moving around and got them to know each other. (2) A “treasure hunt” for living things, in which they plunged their hands into the cold sea water and searched for crabs and hermit crabs. (3) Education to distinguish carnivorous and herbivorous crabs by holding them in their hands and observing them. (4) A game in which children pick up and carry crabs with large claws.

III. Results

Of the 20 preschool children who took part, we were able to obtain and compare drawings made before and after the program from 16 children (six boys and 10 girls). The results of questionnaires given to parents and guardians indicated that five engaged with the sea four or five times a year, while three of the children did not even visit the seashore once a year. Reasons for participating in the education program included: “I want my child to have all kinds of different experiences in a group setting, not only with his/her siblings, but also with other kids.” “I wanted him/her to experience an activity that would not be possible just with family members.” “I want my child to play with friends while interacting with the natural environment.” After the program there was feedback such as: “Joining an educational program that was also a hands-on experience led my child to develop a strong interest in the sea,” “It was a fresh and novel experience he/she could not have had with just the immediate family,” and “He/she was reluctant to touch animals before, but after observing other kids doing so, became able to.” These comments indicate that the program had the desired effect of giving kids a valuable hands-on experience with nature and the sea. When the children’s pictures drawn before and after the program are compared, the most striking difference is whether or not people are included in the picture (Table.1, Table.2). Of the 16 kids who drew both pictures, only one put a person in the picture before the program, but this increased to seven afterward, and six of these depicted “sea animals and me” together. There was also one who drew “sea animals, my friends, and me,” and another who drew a four-panel comic strip telling a story. After the program, all of the children who included a person in the picture afterward were girls. In addition, eight of the 16 children drew living things small and weakly beforehand, but more powerfully and dynamically afterward.

.jpg)

IV. Discussion

Piaget [7] and Luquet [8] collected around a lot of pictures made by children, and studied the developmental stages of these pictures over the course of early childhood. Regardless of country, the stages of development were found to be regular and to follow a consistent path, which can be described as scribbling phase → symbolic phase → schematic phase → pictorial phase → mature phase. Also, Higashiyama [9] has observed that while 93% of young girls’ pictures feature human figures, boys’ are equally dominated by cars and trains. In terms of prior research on changes in the pictures children draw before and after environmental education programs, one study by Tashiro [10] involved teaching elementary school students about agricultural irrigation canals. Tashiro observed that pictures drawn after the program included more human figures, and concluded that more children had come to recognize canals and other agricultural zones as play areas. Yamashita [11] also reported that experiences with nature affect young children’s internal models and heighten their sensitivity. In addition, changes in perspective are seen in children’s pictorial approaches, with some children graduating from the “schematic phase” typical of infancy. It has been reported that further, repeated nature experiences thereafter are correlated with a trend toward larger, bolder depictions of human figures. As we have discussed, observing changes in the pictures children draw, we can infer that the environmental learning programs had an effect, in that children gained cognition of relationships among “the sea, me, and my friends.”

In the future, we will aim to increase the number of case studies of changes in young children’s pictorial expressions before and after environmental learning programs, and to establish a method of gauging the effects of these programs. Also, we will examine whether similar changes are seen in pictures drawn after viewing TV programs or being read picture books aloud.

V. Acknowledgment

I would like to express my gratitude to Takasago Youth House and NPO ”SIMINZU SI-ZU”.

1. United States Department of State, Document : “Limits in the Seas-Theoretical Areal allocations of Seabed to Coastal States,” 1972.

2. T.Yoshio, ” Involvement of new territorial waters Relations Act and the Hydrographic Department,” Quarterly journal, Vol.25, No.3, pp.2-14, 1996.(in Japanese)

3. Basic Act on Ocean Policy, Act No. 33 of April 27, 2007, Article 28 (Enhancement of Citizen's Understanding of the Oceans, etc.)

4. S. Mori, R. Yamanaka, Y. Kozuki, T. Nakanishi, K. Hirai, K. Isshiki, M. Maeda, H. Ueshima, K. Tajiri, and K. Kakiuchi, “Good ripple effect on environmental education with water pollution and water quality improvement as theme in Amagasaki Canal,” Journal of Coastal Zone Studies, Vol.23.No.2, pp.63-74, 2010. (in Japanese with English abstract)

5. A. Denham, Susanne, “Emotional development in young children. The Guilford series on Special and emotional development,” Guilford Press Emotional development in young children, 1998, p.260.

6. S. Knight “International perspectives on forest School: Natural spaces to play and learn”, SAGE Publications Ltd , 2013.

7. J.Piaget, and B,Inhelder, “The Child's Conception of Space,” London, Routledge & Kegan, 1956.

8. G. Luquet, “Le Dessin Enfantin,” Paris, Alcan, 1927.

9. A. Higashiyama and N. Higashiyama “What is the child's picture to show,” NHK Publishing Co., Ltd., 1999. (in Japanese)

10. Y. Tashiro, “Cognitive effects of biodiversity on elementary school students through natural learning experiences: Before-and-after comparisons of paintings,” Research Center for Sustainability and Environment, Shiga University.Vol.9, No.1, 2012. (in Japanese)

11. Y. Yamashita, K. Shiomitu and K.Yaguchi, “A construction of the developmental sequence from preschool to primary school curriculum by The collaborative activity and sensation project in a river,” The University of Shimane junior College, Vol.51, pp.23-32, 2013. (in Japanese)